Farmers prepare for changing climate

Orchardist Guy Ames shared a story of not being prepared for a drought and having to use every container he had to haul water to his trees. The next year he invested in a farm cistern. Photo credit: Ames Orchard and Nursery

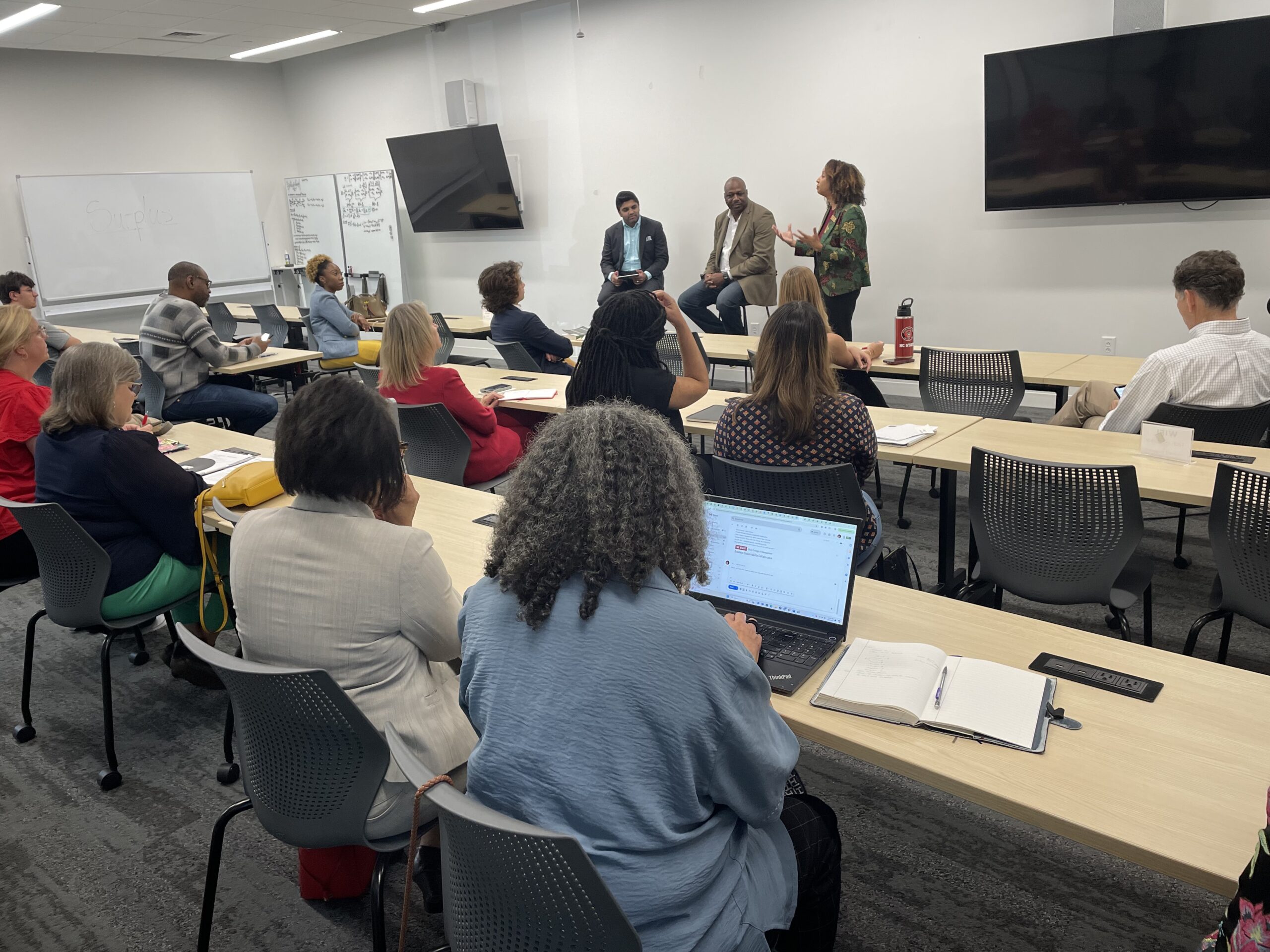

Farmers, researchers and activists gathered in Pittsboro recently to discuss what climate change will mean for North Carolina’s agricultural producers. Abundance NC has hosted the Climate Adaptation Conference annually since 2013 in order to help farmers learn what types of climactic shifts they can expect, share practices that increase resiliency and connect to available resources.

This year, Peter Bane, founder and editor of Permaculture Activist magazine, kicked off the conference with a fiery keynote, explaining in detail how agriculture could stop emitting greenhouse gasses and start sinking as much as 58 billion tons of biologically stable carbon into the soil each year. As farmers increase the organic matter in their soils, they decrease the amount of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere.

Part two of this article will look at agriculture as a potential climate change mitigation strategy. This article will focus on how North Carolina’s climate is likely to shift, and what strategies farmers are using to adapt and increase resiliency.

North Carolina’s Changing Climate

State climatologist, Dr. Ryan Boyles, was on hand to talk about what the scientific data can and cannot tell us about climate change and weather patterns. He explained how temperature shifts in the pacific ocean affects how far the jet stream will dip, which determines how many storms the south east will get. He also discussed how a shift in the Bermuda high pressure system can lead to flooding in Texas and severe drought in North Carolina. However, he admitted that scientists do not know what causes the Bermuda High to move, and therefore can only forecast droughts a few months in advance. Given how hard it is to predict the climate next summer, it is impossible to say exactly what summer will be like in 2055, but Boyles shared some observable trends that will likely continue if humans continue emitting greenhouse gasses at current rates.

So far, the southeast has been relatively sheltered from the effects of climate change. Compared with other parts of the country, we have only seen a moderate increase in average temperature. Scientists are not sure why this is, but many believe it has to do with much of the land being allowed to return to forest as agriculture shifted west. Even so, we are already experiencing warming and Boyle predicts that, by mid-century, North Carolina will have 20-25 more days in the 90’s, and 15-20 fewer nights below freezing. As Boyles puts it, “We’re losing a month of winter and gaining a month of summer,” though the average last frost will likely stay where it is.

According to Boyles, North Carolina will likely get 10% more rainfall by mid century. However, he believes it will come in fewer storms that dump inches of water all at once. There will probably be less snow, but more severe thunder and hail storms. The time between rains is set to increase, causing more regular periods of drought.

Impacts of Climate Change on Farmers

The warmer temperatures and altered rain patterns will have major implications for agricultural producers in the south east. Fewer freezes to kill off insects will likely lead to increased pest pressure. The warmer winter will prompt fruit and nut trees to break dormancy earlier, making it more likely that a late frost will damage delicate buds. The warmer weather does offer a longer growing season, however farmers may need to protect their crops from being oversaturated with sunlight during intense summer heat. Drenching downpours often fail to penetrate soils and recharge aquifers, making less water available to irrigate with during droughts.

Shifts in climate will change what crops are going to thrive in North Carolina, and what growing methods will result in good yields. Many farmers are already experimenting with different adaptation strategies in their fields, but they will need support from research universities and federal agencies in order to navigate through this transition.

The USDA has begun to pay close attention to climate change projections, and the implications they will have on farmers. Dr. Laura Legnick, one of the authors of the USDA’s recent report on Climate Change and Agriculture, was on hand to talk about her forthcoming book, Resilient Agriculture. Staff from the USDA’s Southeast Regional Climate Hub were also present, and shared the work they are doing to help extension agents make informed recommendations regarding climate adaptation.

Agricultural Adaptation Strategies

At the conference, many presenters and farmers shared techniques that they were using to increase the resiliency of their farm. A number of presenters stressed the importance of sinking water into the landscape in order to decrease the need for irrigation during droughts. In the keynote, Peter Bane encouraged every farmer to learn about keyline irrigation, a method of holding water at key points in the landscape and trenching on contour to bring water out to drier ridges. Bobby Tucker followed up with stories of how he has used keyline design on his farm to keep his soils uniformly moist.

A lot of conversations circled around which species and plant breeds will be best suited for the southeast in coming decades. Guy Ames shared a wealth of information about sustainable fruit and nut production. He has spent decades working his orchard in the Ozarks, and knows exactly what types of pests and funguses farmers need to worry about in the southeast. He has lost huge crops to late frosts and insufficient chilling hours, and has had to abandon some varieties that repeatedly failed to produce. He suggested particularly resilient varieties of common tree fruits, but admitted that warmer temperatures would make it increasingly difficult for southeastern orchardists to produce marketable apples and peaches without relying heavily on chemical sprays. Ames suggested farmers experiment with less traditional fruits that grow well in warmer climates, like pawpaws, jujubes and Chinese mulberries (which can be grafted onto osage orange roots). Though customers may not be familiar with these fruits, they are delicious enough to sell themselves and hardy enough to survive fluctuations in weather.

Paul Blundell, of Southern Exposure Seed Exchange, explained why regional, distributed seed research is critically important for adaptation. When farmers use seeds developed in other regions, those seeds are not bread for resistance to the pests and mildews of the southeast. One of Southern Exposure’s seed farmers recently received a USDA Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education grant to study powdery mildew resistance in open pollinated varieties of cucurbits. However, most breeding research is focused on developing new hybrid varieties, which prevents farmers from saving seeds and developing better-adapted breeds. Local plant breeder Doug Jones was on hand with pepper seeds he’s bred specifically for the Carolina Piedmont. More breading efforts like his could provide farmers with seeds that are well suited to the particularities of our region.

In response to more intense summer heat, Bane suggested farmers start planting trees. Traditionally croplands have been cleared of trees, but new research demonstrates that most plants become oversaturated with sunlight during long summer days, and actually grow better in partial shade. Trees planted the right distance apart can still provide sufficient sun for ample crop or grass growth, and help the soil retain moisture.

Dr. Lengnick offered inspiring stories of how farmers around the country were becoming more nimble, learning to grow different crops for various weather scenarios. She challenged the notion that local was always better, and offered a vision of diverse, regional food systems, oriented around major metropolitan areas. Given our inability to accurately predict how our climate may change during this century, diversity will be critical as we try and determine what kind of agriculture is appropriate for the southeast in the 21st century.

Many presenters emphasized that developing deep, healthy soils was the single most important way to increase farm resilience. Well-structured soils with high levels of organic matter allow water to penetrate and retain moisture long after a rain. A 1% increase in soil organic matter allows soils to hold an additional 16,500 gallons of water. And, as the second part of this article will explain, building healthy soils has that added benefit of sequestering carbon and mitigating climate change.

- Categories: