FINANCING THE FOOD SYSTEM: HOW SLOW MONEY GROWS LOCAL FOOD

Cows at Lilly Den Farm. An affordable Slow Money Loan helped farner Tucker Worthington purchase a used skidsteer, instead of renting one. Photo: Bett Wilson Foley

By Sami Grover

“When you run a small business for years, it’s like you see a snapshot of what is going on with the wider economy.”

That’s how Carol Peppe Hewitt describes her entry point into Slow Money.

She had been running a successful artisan pottery business with her husband Mark for decades, and observed how hard it was for small businesses to access affordable credit. This was particularly true within the local food movement – where farmers, small processors and producers were unable to get loans to start up or expand their business.

CONSUMERS BECOME INVESTORS

At the same time, Carol noticed a desire among local food devotees – the customers at farmers’ markets, restaurants and food co-ops – to do more to expand the movement. “I just can’t eat enough local food to create the kind of change I wish to see,” they’d say. “Surely there are other ways to help?”

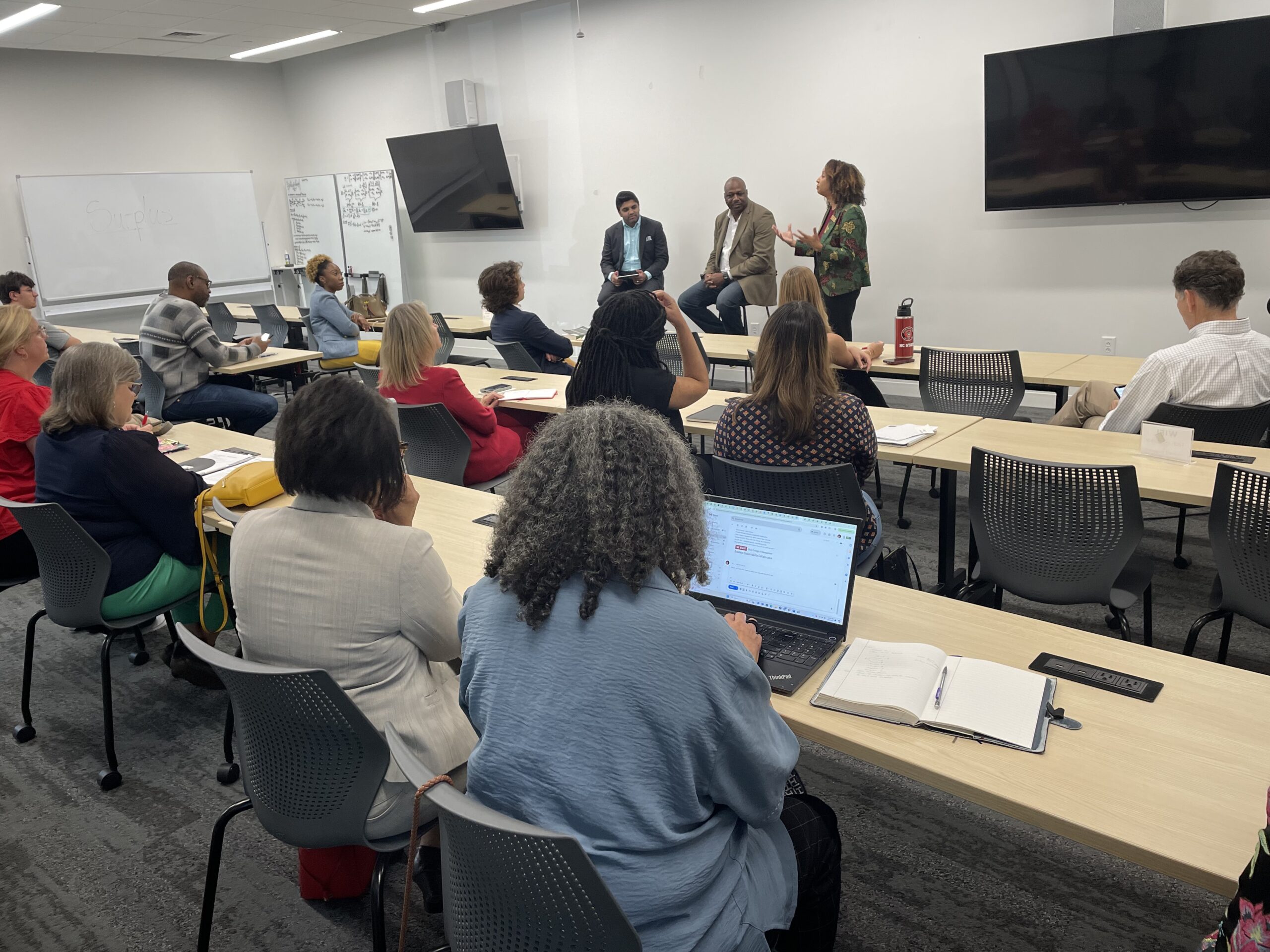

The threads began to come together when Woody Tasch – the founder, chairman and president of Slow Money – came to talk at a local community college to an audience of about 30 people.

THE POWER OF MONEY

“Woody described a concept that was simple and yet revolutionary,” Hewitt explains. “He talked about reclaiming the power of our money. Taking it out of the stock market and instead facilitating small, peer-to-peer loans at affordable rates. Putting money into businesses that provide real world benefits for our communities.”

The talk ignited intense discussion in the audience. Several attendees – including Lyle Estill of Piedmont Biofuels and Jordan Puryear of Shakori Hills Festival – formulated plans to to get a Slow Money chapter started in NC.

“Many of us had already made personal loans to businesses we believed in. It seemed like the logical next step to formalize this approach so that we could empower others to do the same.”

Goats at Lilly Den Farm. Photo: Bett Wilson Foley

Not long after, Slow Money NC was born, making its first $2000 loan to Lynette Driver – a local baker looking to buy a mixer – and a second loan of around $6000 to fund the expansion of Angelina’s Kitchen – a Greek restaurant in Pittsboro serving local, sustainable food.

BUILDING AND MAINTAINING FERTILITY

The focus that the Slow Money movement has on local food and sustainable agriculture is no accident.

There is a direct lineage to the Slow Food movement which began in Italy and has spread globally as an antidote to perceived global dominance of the fast food industry – seeking instead to preserve diverse food traditions and promote sustainable, small-scale agriculture.

“Slow Money is a natural next step for many Slow Food supporters. It is explicitly about building and maintaining the fertility of our soils.” says Hewitt. “They say that mankind owes its existence to six inches of topsoil and the fact that it rains. It seems like that might be something worth investing in.”

MEETING PRACTICAL NEEDS

While the movement undoubtedly has ideological and ecological underpinnings – its focus remains on the real world needs of small food related businesses. From encouraging sustained, predictable and long-term loans to ensuring that rates remain affordable (the typical loan rate is between 2-5%), Slow Money advocates argue that it has to be about more than just securing alternative sources of money – but rather rethinking the entire process and terms of how it is leant.

Mark Scharaga is the founder and owner of Tamashii Sushi and Spoons Restaurant in Wilmington – which describes itself as the first and only sustainable sushi restaurant in the Southeast. Scharaga used a Slow Money loan to finance a state-of-the-art water filtration system as an alternative to bottled water for his customers.

He came across Slow Money after a loan officer at his local bank referred him to the group. While the concept may be new, he suggests, it is in many ways a return to an older model of finance. “The lenders are driven by a belief and a trust in the people they are supporting. It’s not about your credit rating, but about the mission and vision of your business. What you are trying to achieve.”

Tamashii Sushi and Spoons used a Slow Money loan to finance a new water filtration system.

BANKS DON’T UNDERSTAND FARMING

The willingness of lenders to understand the real needs of the business is something that has also proved invaluable to Casey Lance of Transylvania County, who together with her husband Mike expanded Calee’s Coop Farm from a hobby chicken farm into a full time operation with 500 chickens and 15 hogs.

“Banks just don’t lend to small farmers,” she says. “They don’t understand us. They can’t provide terms that work for our business model. It’s just not a good fit.”

Casey Lance with her daughter, Calee. Photo: Jessica Nolan

After a group of Slow Money advocates came to speak at the local Tailgate Market committee, Casey and Mike decided to explore Slow Money as a source of financing an additional coop.

HASSLE-FREE LENDING AND BORROWING

“The process couldn’t have been simpler,” says Casey. “The lenders were customers of ours. They came and visited the farm – took a look at our plans. And then we met up again to sign some paperwork. All the red tape took just half an hour to complete.”

The relatively informal process and low overheads are central to the Slow Money model. For reasons both legal and practical, all loans are explicitly a private arrangement between friends, family and community members who know each other. Slow Money merely acts as a matchmaker and an advisor – providing a framework that ensures the loans work for everybody. And early success seems to be generating additional interest.

“Having watched our experience,” Casey explains, “we are seeing many other farmers taking an interest in Slow Money. Several more loans are in the works in our county.”

Interestingly, the financial benefits are not simply a one way street. While investors may not get the kind of interest rates charged by traditional banks, they still yield competitive interest rates with, so far at least, a good track record of repayment.

“These loans tend to perform very well,” says Hewitt. “From the borrowers perspective, this lender is someone you know who has put their faith and their personal resources into helping you realize your dream. Even when they are in a pinch, more often than not, a borrower will pay this loan first, over other expenses. Of the $580k+ that we have loaned to date, only $5k is considerably behind in making payments.”

SMALL LOANS YIELD BIG DIVIDENDS

Quantifying the impact of a group like Slow Money NC is always tough. At the time of going to press, there were a total of 24 loans completed and over $581,000 lent. But that big monetary figure obscures the real value of the approach. Says Hewitt, “The cumulative amount we’ve lent is a little deceptive,” she explains. “Over $400,000 of that was a single loan aimed at refinancing our local co-op grocery store in Chatham County. Most of our other loans are for a few thousand dollars. A beehive here. A mixer there. Believe it or not, these small amounts can make all the difference.”

And Hewitt may be onto something here. There is evidence from other farm-focused loan programs that there are substantive knock on benefits from relatively small investments.

Tomatoes from Lilly Den Farm. Photo: Bett Wilson Foley

LOCAL FOOD AS ECONOMIC STIMULUS

In 2011, for example, a report by UNCG researchers into the Rural Advancement Foundation International’s (RAFI) Tobacco Communities Reinvestment Fund suggested that a small-scale loan program – with loan amounts averaging around $10,000 – could yield substantial economic returns. RAFI explained the numbers in a blog post as follows:

- Each of our grants created an average of 11 new jobs within one year.

- For every one dollar awarded to a farmer, they traced $205 new dollars of economic activity in the state within one year.

- In total, the program awarded $3.6 million in three years to 367 farmers, created 4,100 new jobs, and had an economic impact of more than $733 million.

It’s not just farms themselves that have the power acting as economic multipliers for small investments. Small, local food businesses of all types can have the same ripple effect across the communities they operate in. At least, that’s the hope of Kathryn Beattie of Leading Green Distributing in Black Mountain, who is in the process of applying for a Slow Money loan to insulate and refrigerate a new biodiesel-powered van. Kathryn, whose business serves between 12 and 40 farms by delivering their produce to local markets, hopes that a relatively small loan will make a big difference to the impact they can have:

“We’re probably talking in the region of $8,000 to $12,000 that we need. It really doesn’t take a lot of money to lift companies like ours to the next level.”

TRANSCENDING POLITICS

Anyone who has watched an episode of Portlandia will know that the local food movement is often perceived as a liberal, elite concern. But Hewitt argues that this is a misconception. Slow Money, she suggests, can act as a forum for transcending traditional cultural and political divides. “We held an event at Market, a restauraunt in Raleigh, the other week. Folks came from all over the surrounding community. I have no idea what their political leanings were. It just doesn’t come up. They came because there was talk of a coop grocery store opening in their community, and they had an interest in seeing it succeed.”

GROWING THE MOVEMENT

What comes next for Slow Money remains to be seen – but Hewitt seems sure that the concept will continue to grow. “Check back in with me before you publish,” she laughs. “The number of loans and amount we’ve lent will almost certainly be out of date – we’re making new loans all the time.”

On a national scale, the Slow Money movement has set a goal of encouraging 1 million people to invest just 1% of their wealth in local food and farming enterprises in the next decade. Whether or not they succeed remains to be seen, but Hewitt seems determined to do her part to make it happen.

In fact, she has a book coming out in the Spring aimed at spreading the movement to other regions. She describes her vision for Financing Our Foodshed: Growing Local Food with Slow Money (available for pre-order now) as being a little like “young adult reading” for advocates of localization:

“I want someone to pick this up in Wisconsin, or wherever, and think – This is simple. I can do this here too.”

If the Slow Money movement in NC continues to enjoy the success it has so far, then the chances are that other states won’t be far behind.

MORE ARTICLES ON LOCAL FOOD IN NC

Sustainable Craft Brewery Earns Recognition in Eastern NC

From Industrial Eats to 95% Local Ingredients: One Chef’s Journey

Market Helps Revitalize Downtown Burlington