Is the Piedmont ready for rabbit?

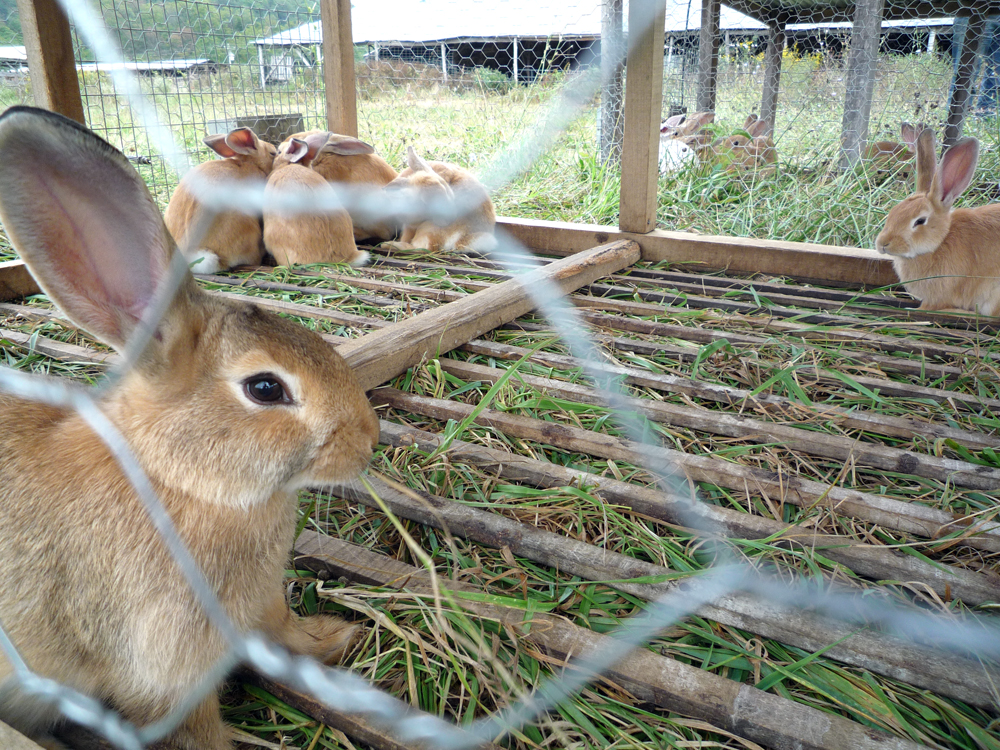

Pastured rabbits at Polyface Farm in Virginia. Photo credit: Jessica Reeder

Rabbit is a popular menu items at many local food restaurants in the Piedmont, but a lack of local certified processing facilities prevents farmers from meeting the demand locally. Rabbit raisers, like Mary DeMare and Dan Shields of Fatty Owl Farm, can sell their farm-processed meat directly to customers, but not to anyone who will re-sell it, like restaurants, catering companies or food trucks. Chefs wanting to include North Carolina rabbit on their menu must purchase it from a North Carolina Department of Agriculture (NCDA) certified processing facility in Asheville, four hours away from the Triangle’s thriving local food scene.

Fatty Owl Farm has set out to change that with a BarnRaiser crowdfunding campaign to finance their own NCDA-certified processing facility. With 26 days left, they are more than two thirds of the way to their $10,000 goal. The new facility will be located on their Chatham County farm, and other Piedmont rabbit-raisers will be able to have their rabbits processed there as well. There is no shortage of demand for local, sustainably-raised rabbits, and DeMare and Shields have already begun teaching other farmers and homesteaders how to raise and process this delicious, nutritious and ecologically friendly source of meat. Chefs dedicated to sourcing local, like Isaiah Allen of The Eddy Pub, are excited to start incorporating fresh rabbits from nearby farms into regional cuisine.

The Appeal of Rabbit Meat

Chefs and restaurant-goers love the flavor and texture of rabbit meat, but it is also one of the most-sustainable and healthiest farm-raised meat. Rabbits have a relatively low feed conversion efficiency ratio, meaning it doesn’t take much feed for them to gain weight. Grain feeds are expensive, both to farmers and to the environment. For a cow to gain a pound of weight, a farmer needs to feed it about eight pounds of grain. The water and chemicals used to grow this grain, as well as the fossil fuel used to process and transport it, are all part of ground beef’s overall environmental impact. A rabbit puts on a pound of weight with only three to four pounds of feed, making it half as ecologically costly as grain-fed cows.

Raising rabbits can be an incredibly efficient use of space, making it ideal for urban and suburban farmers searching for a sustainable way of offering neighbors a healthy source of protein. Though rabbits raised in high-density by themselves can smell terrible and be a dangerous breeding ground for bacteria, Daniel Salatin, of Polyface Farms, developed a Racken House that puts rabbits on top of chickens, allowing the chickens to clean up scraps and mix the manure into wood chips, creating a well-balanced compost.

Rabbit manure is a notoriously good fertilizer for plants.

Rackin Farmer from Kristin Canty on Vimeo.

Chickens and rabbits have a symbiotic relationship, making them well suited to be raised together. According to Daniel, “One of the neat principles of the Racken House is we can raise more pounds of meat per square foot than a confinement operation of a monoculture of straight chicken or rabbits, but neither one of the animals are at a tipping point for pathogens and disease.” Polyface’s racking house is about the size of a three car garage, and offers 150 eggs per day and 1000 rabbits per year.

On more rural farms like Polyface, rabbits can also spend part of their life feeding on pasture. However, most meat-rabbits have been bread to survive on grain rather than native plants and grasses. In order to develop a forage-based breed of meat-rabbits, the Salatins had to spend almost twenty years allowing the rabbits that thrived on pasture to reproduce at higher rates. Now they sell their breed of rabbits to other rabbit raisers who want to transition away from grain feed. One of Polyface’s rabbits’ favorite food is comfrey, a nutrient-dense plant that is almost impossible to kill.

If rabbits’ low ecological foot-print isn’t enough of a selling point, rabbit is also one of the healthiest meats around. It has a higher protein content than meat or chicken and is low in fat and cholesterol. It is rich in vitamins and nutrient-dense. Chefs love the diversity of textures and flavors that a single rabbit provides. Rabbit was commonly eaten all over America until the birth of industrial poultry operations sixty years ago. The taste alone is enough to keep most people who have tried rabbit coming back for more.

Piedmont Diners Demand Local Rabbit

Facing a saturated poultry market, Fatty Owl Farm started raising rabbits in 2012. They sell their rabbits at farmers markets and offer workshops where they teach farmers and homesteaders everything they need to know about raising a processing rabbits for themselves. Restaurants like The Eddy Pub in Saxapahaw and Angelina’s Kitchen in Pittsboro are anxious to add Fatty Owl rabbits to their menu, but the couple has no interest in hauling their rabbits all the way of to Asheville for processing.

DeMare explained in a recent interview, “We care about every minute of the lives of our animals. The end of life needs to be as stress free, quick and painless as possible. Unless we are doing it ourselves, there is no way to ensure that is the case.”

Their NCDA-certified processing facility will also serve as a teaching space where they will continue to teach how to raise and process rabbits. Other nearby rabbit-raiser will be able to bring their rabbits to the facility, do the processing themselves, and then sell their rabbit to food resellers, like restaurants, catering companies and food trucks.

Fatty Owl hopes that the processing facility will help reestablish rabbit as an important meat source in the Carolina Piedmont, as it was before the invention of industrial poultry operations. Rabbit dishes are already common in restaurants that specialize in regional cuisine, and small-scale meat producers are anxious to meet the demand for local rabbit. With twenty-seven days left in their campaign at the time of writing, Fatty Owl Farm needs only $3,500 more to successfully fund their new processing facility.

- Categories: